Deep Dive: Jones Road Ground Water Plume Superfund Site

The EPA is launching a series of tests in the community surrounding the Jones Road Ground Water Plume Superfund Site. In February of this year, the EPA awarded a $3.2 Million contract for a “supplemental Remedial Investigation/Feasibility Study (RI/FS) focused on delineating the vertical and horizontal extent of the groundwater contamination and determine the feasibility of the 2010 Record of Decision (ROD) selected remedy, pump and treat.” That means a contractor will study how deep and how wide the plume of toxic chemicals has spread in the aquifer and the best way to clean it up. Before much of that work can even start, the agency will be asking homeowners for permission to perform soil and groundwater testing.

To understand why it is so important for residents to cooperate with the tests, we need to explain a little bit about how the dry cleaning chemicals that make the Jones Road site so hazardous interact with the environment, especially how groundwater plumes can carry those chemicals beneath neighborhoods.

You may want to put on your waterproof boots, because we’re getting ready to wade into some pretty deep science here.

What Happened At Jones Road?

Bell Dry Cleaners operated for nearly 20 years in the strip mall at 11600 Jones Road in Northwest Houston. In 2000, while testing water at a nearby daycare/gymnastics school, the state detected chemicals including Tetrachloroethene (PERC) used in the dry cleaning process. Tetrachloroethene is a likely carcinogen that has been linked to problems with pregnancies and unborn children, breathing problems and neurological effects.

No one knows how much of the contaminated liquid was dumped, but the chemicals found in the water well that supplied the children’s gymnastics facility led to the discovery of the dry cleaners' illegal dumping practices. Authorities drilled monitoring wells right around the site and found contamination in eight locations, with concentrations starting just a few feet below the strip mall.

The site was added to the EPA’s Superfund Priority list in 2003. Government reports estimate that roughly 19,000 people live in nearly seven thousand residential housing units within one mile of the site. The plume lies below those homes and, unfortunately, many of the residents get their water from private wells.

PERC and Water Plumes

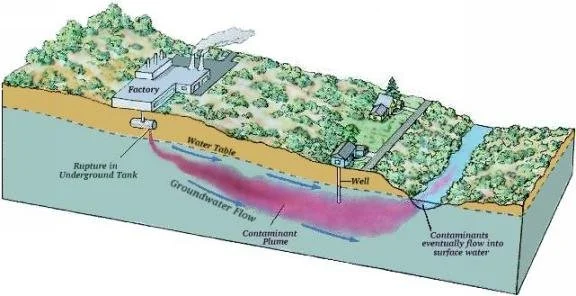

A groundwater plume is what happens when contaminated material gets into the aquifer and moves in the direction of the water flow.

Except it never looks as simple as it appears in diagrams.

The aquifer isn’t an underground pool of water. On the Upper Texas Coast, it’s basically soil that is able to contain water. The amount of water it holds depends on composition of the soil, materials like sand, gravel, limestone and fractured rock. It’s less like a cup of water and more like a muddy sponge.

The liquid that makes up the plume doesn’t flow like a river. It can move very slowly and even change direction, depending on pressure from water being drawn or entering the system.

The ground isn’t consistent. Different material or consistency creates different layers of the aquifer. The plume may be located higher or lower depending on the makeup of the soil.

PERC is denser than water, which means it sinks, but it won’t sink very fast into the aquifer (remember, there is all that other material down there). It also starts to degrade once it is in the water but that can take a long time, as shown by the fact that it still shows up in water wells after being in the ground for 25 years.

If PERC degrades, that's a good thing right? Wrong, because it degrades into trichloroethylene (TCE), dichloroethylene (DCE) and then Vinyl Chloride, three chemicals that can be even more hazardous than the original PERC.

And This Is All Taking Place In The Aquifer Where People Get Their Well Water.

Removing chemicals from water can complex and time consuming. That’s why the EPA has focused on trying to get people to stop using well water, even paying for people to hook up to municipal water. However, that effort has had only limited success.

Now the EPA is finally ready to focus on removing the chemical contaminants from the water supply. The first step is to figure out exactly where those chemicals are. Over the last 25 years, the plume has moved and now may include houses that were not in the original toxic threat zone. It has also sunk deeper in some areas. Because wells are drilled to specific depths, that means homes that were not at risk may be at risk in the future as the plume shifts.

To date, the EPA has found contamination in the shallow and deep water zones through its own monitoring wells and from samples of private water wells.

The Next Phase Will Be Important.

The contractors will sink additional monitoring wells and reach out to homeowners for permission to sample from additional private wells. They will also create 3D visualization of the aquifer to help map out the changing shape of the groundwater plume in terms of location and depth.

It has taken longer than it should have, but the EPA is finally focused on a solution that could protect residents from a contamination problem that has haunted the area for decades. That’s why it’s critical for the community to stay engaged and for homeowners to allow investigators to access water sources. You can’t clean up what you can’t find–and without knowing where all the contamination is, the agency can’t truly protect public health.