New Report Should Give Houstonians A Sinking Feeling.

Houston made national headlines this month for something no city should want. Houston and the surrounding area is sinking faster than any other big city in America.

What Does It Mean?

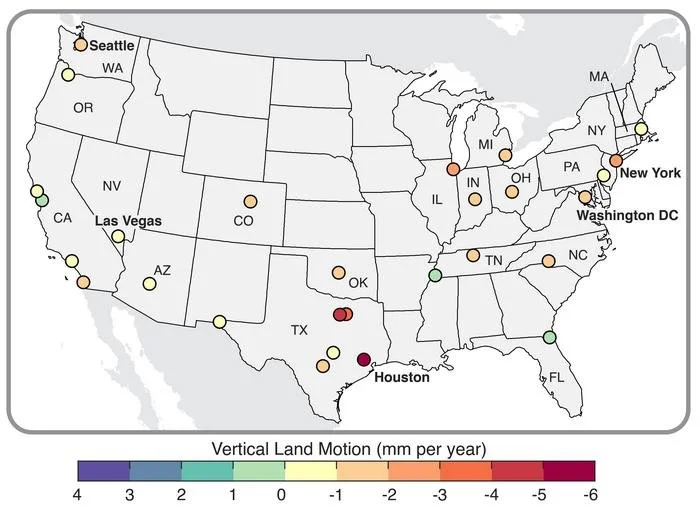

The study by the Columbia University Climate School compared the subsidence rates (also called vertical land movement) for the top 28 cities in the country. It used satellite-based radar measurements to calculate how fast land in the cities was rising or falling.

Adapted from Ohenhen et al., Nature Cities, 2025

Researchers found that Houston was at the top of the subsidence list, and Dallas and Forth Worth ranked second and third.

The dictionary definition of subsidence is: sinking of the Earth’s surface in response to geologic or man-induced causes.

In Houston’s case, the study found that in 40% of the city, land is sinking at a rate of at least one inch every five years. However, some areas are sinking at 10 times that rate. There is geologic evidence that the Houston area has been subsiding for the last 4,000 years as the land settles, but the natural subsidence has been very slow. The consensus is that the natural subsidence has been less than a millimeter a year, or less than an inch every 25 years.

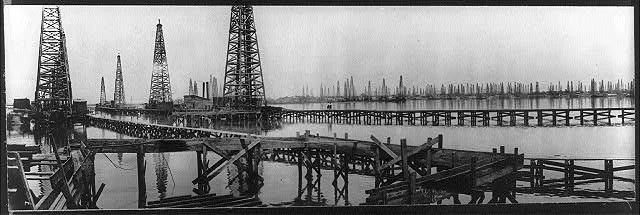

Why are we sinking so much faster now? The two main culprits are removal of water from the aquifer and oil and gas production. In the case of the Houston area, wildcatters started drilling oil locally 120 years ago.

The Goose Creek Oil Field near Baytown has produced more than 150 million barrels of oil since its discovery, but the price was to cause the land to sink by three feet, turning residential land into part of San Jacinto Bay.

However, it’s the water we’ve pumped that has had the biggest impact over the broadest area of the region.

It’s not hard to wrap your head around the idea that water removal affects land elevation. Just imagine yourself sitting on top of a bag full of water while you sip water through a straw. The more you drink, the more you sink.

What This Means To You

The weight of buildings and pavement can cause localized subsidence, especially in areas with loose soil. This is a problem that local homeowners know all too well.

Think about this….Houston has more than 6,000 miles of sewer systems that rely on gravity to operate, meaning the sewage that goes into the line needs to be higher than the end of the system. If subsidence causes the entrance to the pipe to be lower than the end of the pipe, the sewage will flow backward. Ewwwww!

One approach to subsidence is to pump water back into the aquifer. However, there is evidence that this releases arsenic, lead and dissolved solids from the soil into the water, raising the threat of contamination.

Subsidence increases Houston’s flooding threat. Even as our land sinks, we face increases in severe rain events and rising seas. If your house used to be a foot above sea level and it is now six inches lower, the chances of an extreme storm or high tide flooding your home magnifies.

Houston’s Toxic Subsidence Problem

Finally, subsidence can make us sick, especially in communities near contaminated toxic waste sites.

Rice University researchers identified nearly 2,000 shutdown and forgotten industrial sites that may contain chemical contamination that could flow through neighborhoods as local flooding increases. THEA has been in the forefront of warning about the threat from Houston’s toxic legacy and flooding.

Subsidence is a serious concern for the known Superfund Sites in the Houston/Galveston area. A good example is the Highland Acid Pit Superfund Site. When a site review was performed in 2018, the elevation at the site was 5-10 feet above sea level. Today it is about 4-7 feet above sea level even as highwater events on the San Jacinto River have been on the rise.

Subsidence and increased storm events are issues in most cities, but in Gulf Coast cities like Houston you can add the threat from Hurricanes. We saw this very clearly during Hurricane Harvey when several local Superfund Sites were completely submerged by the heavy rains and high river stages we experienced. This was shockingly apparent on the San Jacinto River where the raging currents tore through the temporary cap on the Waste Pits Superfund Site, allowing dioxin material to flow into the river. A month after the storm, the EPA found nearby dioxin levels that were 2,000 times higher than safe limits.

How Much Does Subsidence Impact Toxic Releases?

Unfortunately, no one knows. That’s because there is no coordinated effort to find out. Take North and South Cavalcade Superfund Sites, two sites that lie less than a mile apart beside the Greater Fifth Ward. Work still needs to be done to make the North site safe and in its last review of the South site, the EPA said it needed to determine if chemicals were still seeping from the site before it can say whether public health was being protected. Even though subsidence in the area is relatively stable, it is impossible to say when a change of an inch or two might make the existing remediation safeguards inadequate.

How Do We Make Sure Subsidence Doesn’t Threaten Our Environmental Health?

First and foremost, the EPA needs to move forward with the existing Superfund cleanups. That means removing the current unaddressed threats at the San Jacinto Waste Pits and the Jones Road Ground Water Plume Superfund Site in Cypress, where subsidence levels are extraordinarily high.

Second, the EPA needs to reassess toxic sites in light of the impact that subsidence, storms and rising sea levels have on sites that have already been remediated. The agency has already started down that path; in its last review of the Highland Acid Pit Site, officials said they need to look whether the existing controls are still effective in light of sinking land and increased flood potential. However, the EPA is moving too slowly. Harvey put the site underwater in 2017 and project managers hope at best to perform the review by 2027, a full decade later.

Finally, Houston and the surrounding communities need to understand the connection between subsidence, flooding and toxic exposure. We need to make assessment and prevention of toxic releases a priority and, so far at least, local and state officials don’t appear to even be aware of the need for action